|

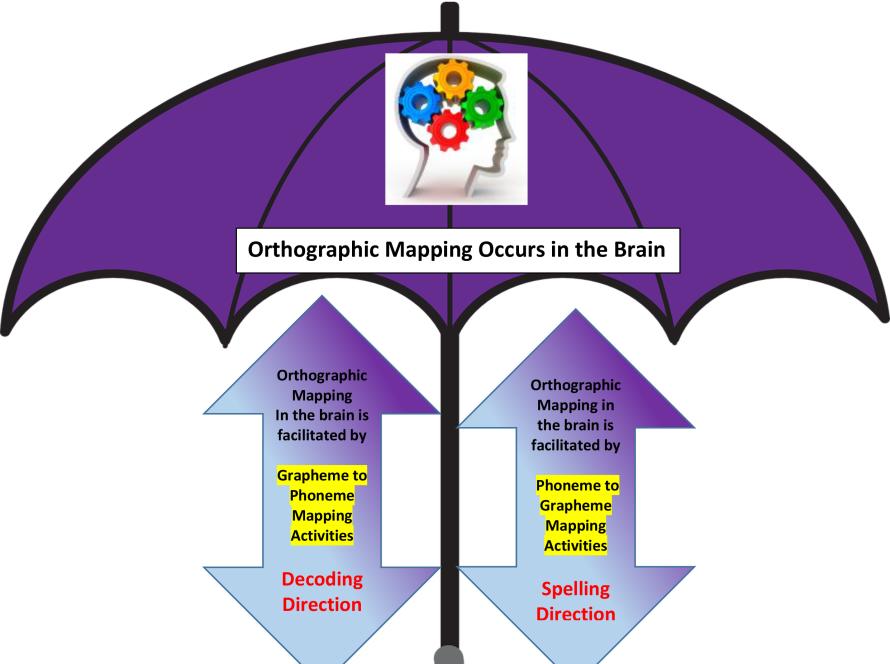

1700s–Mid-1800s: Children are taught to read through memorization of the alphabet, practice with sound-letter correspondences, and spelling lists. The prevailing texts used for teaching reading are the Bible and political essays. Mid-1800s: Inspired by Jeffersonian democratic ideals, some educators attack phonics and urge a meaning-based approach to learning to read. Late 1800s: All-purpose reading materials are replaced by graded readers designed to match a child’s age and ability. 1930s–1970s: A look-say or whole word (not whole language) approach, exemplified by the “Dick and Jane” reading series, dominates reading instruction in schools. Instruction emphasizes comprehension. 1957: Rudolph Flesch’s best-selling book, Why Johnny Can’t Read, urges a return to phonics instruction. In a sharp political and emotional attack, Flesch accuses the whole word approach “of gradually destroying democracy.” 1960’s Elkonin boxes were first used by Russian psychologist D.B. El’konin in the 1960s. El’konin studied young children (5 to 6 years old) and created the method of using boxes to segment words into individual SOUNDS. 1967: Jeanne Chall’s book, Learning to Read: The Great Debate, is published. Chall continues to advocate for direct instruction in phonics. 1970s: The whole language philosophy, which has diverse intellectual roots in Australia, Europe, and North America, emerges. The philosophy promotes a meaning-based approach to learning to read. Mid-1970s: Research on reading shifts from a focus on texts to an emphasis on how readers construct meaning. 1983: Jeanne S. Chall republishes “Learning to Read: The Great Debate,” with new research findings strengthening the case for phonics. 1983 – Kathryn Grace created Sound Boxes and Sound Box Mapping (later named Phoneme-Grapheme Mapping) to use with her struggling readers and spellers in her Vermont classroom. 1984: The National Academy of Education releases Becoming a Nation of Readers, a report on the status of research in reading education. 1984 – Reading Recovery was first introduced in the United States through the Ohio State University by Gay Sue Pinnell and Charlotte Huck. That year Marie Clay and Barbara Watson came to Ohio to begin teaching one trainer, three teacher leaders, and 13 teachers. It was several years before the program and its techniques become wide spread across the United States. 1985 – Mary Clay and Barbara Watson came to Ohio to begin teaching one trainer, three teacher leaders and 13 teachers. Marie Clay introduced Elkonin Boxes as a part of writing during her reading recovery lessons with children. Classroom teachers saw the value of the tool and wanted to use them in their classroom writing as well. 1987: Educational leaders in California, through the state’s English/Language Arts Framework, institute a large-scale, statewide adoption of Whole Language as the method for teaching beginning reading in the state’s grade schools. Many states follow California’s lead. 1988: Researcher Marie Carbo reanalyzes Chall’s earlier research on reading, calling some of the data analysis into question. A lengthy research debate ensues. 1990: Beginning to Read, a landmark study by psychologist Marilyn Adams, analyzes the role of phonics in beginning reading programs. The book fuels controversy over the nature of reading instruction. 1990’s: Brain research using functional MRI (fMRI) shows that the brain reads sound by sound. 1991 – Kathryn Grace copyrights Phoneme/grapheme mapping also known as Sound-Spelling boxes; Sound Boxes for spelling; sound boxes 1992 – Kathryn Grace completes a three year Post Master’s Program at St. Michael’s College in Colchester, VT. She received a Certificate of Advanced Graduate Study (CAGS) in Language and Learning Disabilities where she studied under Dr. Reid Lyon and Dr. Louisa Cook Moats, leading researchers in the field of literacy at the time. Kathryn’s thesis was entitled, “The Effect of Decoding on Reading Comprehension”. 1993: The National Assessment of Educational Progress [16], a federal study doing a state-by-state comparison of reading proficiency, ranks California fourth-graders fifth from the bottom among the fifty states. Three years later, gobsmacked Californians find they are ranked at the very bottom (just behind Mississippi). An astounding 77% of fourth graders are ranked “below grade level.” [17] 1993: 40 Professors of Linguistics in Massachusetts write a letter to the State Commissioner of Education to protest the attempted introduction of Whole Language. 1993 -2015– Kathryn Grace began teaching the TIME for Teachers Course at the Stern Center which incorporated her Phoneme/Grapheme Method into the trainings. 1994: Low reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in California lead to a pro-phonics backlash against the whole language movement. Mid-1990s: Studies released by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health indicate that children with reading difficulties benefit from explicit phonics instruction. Researchers believe the findings support phonics instruction for all students. 1995: California adopts two statutes known as the “ABC” laws, which require, in part, that the state board of education adopt instructional materials, including “systematic, explicit phonics, spelling, and basic computational skills.” 1996: President Clinton launches the America Reads Challenge, a program to address national literacy concerns. Legislation corresponding with the initiative identifies reading instruction as a “local decision.” 1997: The Clinton administration proposes a voluntary national test of 4th grade reading ability. 1997: Several California school systems are charged with violating the ABC statutes by using state funds to purchase non-approved whole language instructional materials. Late 1997: A study on the prevention of early reading difficulties, conducted by the National Academy of Sciences, is slated for release. 1997: Reading instruction continues to generate debate from local to national levels. 1998: Reading researcher Linnea Ehri proposes four phases of sight word learning [18]. Her studies reveal that it is only when beginning readers can form “complete connections” between all the letters (graphemes) seen in a word’s written form and all the sounds (phonemes) heard in its spoken form, that sight word learning becomes unconscious and automatic – a process she calls orthographic mapping. (Kathryn Grace had already created phoneme/grapheme mapping in 1991 and sound boxes before that in 1983). This re-emphasizes the importance of knowing grapheme/phoneme correspondences and being able to blend (decode) unknown words by sounding them out. Share’s Self-Teaching Hypothesis and Ehri’s Orthographic Mapping complement each other. Both theories are in direct opposition to Whole Language. 1997 – 2000: The US Congress convenes a National Reading Panel with the mandate to examine all reputable scientific research available on how to teach children to read, and then to determine the most effective method. The Panel’s members examine several hundred studies conducted in the previous 3 decades. After three years of effort 1999: Dr. Reid Lyon of the National Institute of Health (NIH) reports to Congress on the findings of research on over 34,000 children —findings include the importance of phonics and phonemic awareness for teaching reading. (I studied under Dr. Reid Lyon at St. Michael’s College from 1993-1995 and sometimes taught his graduate courses when he was on speaking engagements. This was before his job at NIH.) 2000 – The National Reading Panel completes its 480-page report, delivering a strong rebuke to Whole Language proponents. It concludes that “systematic” phonics, not Whole Language, is the best method for teaching beginning readers – and that such phonics must be taught explicitly, rather than on a “discovery” or “as-needed” basis. It also concludes that the best time to teach phonics is in kindergarten or first grade (the traditional start of formal reading instruction), before a child starts to read by other means.The report states the following key points: “Systematic phonics instruction makes a bigger contribution to children’s growth in reading than alternative programs providing unsystematic or no phonics instruction.” (2-92) “Teaching children to manipulate phonemes using letters produced bigger effects than teaching without letters. Blending and segmenting instruction showed a much larger effect size on reading than multiple-skill instruction did.” (2-29) 2000 – Present: Many members of the education establishment (the ILA, the NCTE, professors in teaching colleges, many school administrators) do not react favorably to the National Reading Panel’s final report. However, the Panel’s multiple recommendations in support of systematic phonics can’t simply be ignored – many parents and legislators are clamoring for a “return to phonics.” What happens is that the name, “Whole Language,” vanishes from the education scene and from education journals. What takes its place is called “Balanced Literacy” or “The Balanced Approach.” 2000’s: Brain research shows changes in the brain and reading improvement when phonics is taught to poor readers. [21] [22] 2001: No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation passed. The Reading First portion of NCLB mandates phonics instruction. 2002 – Presenter at Vermont Reads Institute Summer Literacy Institute sponsored by the Vermont Reading Recovery Consortium – “Making Spelling as Easy as 1-2-3: The Phoneme-Grapheme Connection and its Place in the Spelling Sequence” 2002 – Kathryn Grace presents at IDA in Atlanta, Georgia. Presentation entitled, “Phoneme-Grapheme Mapping – Explicating Sounds, Symbols and Their Connections” 2002 – The Stern Center put TIME for Teachers online and showcased Kathryn Grace’s Phoneme Grapheme Mapping as a method for teaching the Alphabetic Principle to teachers. 2003 – Kathryn Grace was a presenter at IDA in San Diego, California – Presentation entitled “Bridging Sounds to Print through Phoneme-Grapheme Mapping”2003: Kathryn Grace signs publishing agreement with Sopris West to publish Phonics & Spelling through Phoneme Grapheme Mapping 2004 -– Kathryn Grace copyrights first manual for Phoneme/grapheme Mapping also known as Sound-Spelling boxes; Sound Boxes for spelling; sound boxes (Creation date 1991 before Ehri’s use of the term orthographic mapping. 2004 – Kathryn Grace is a presenter at IDA in Philadelphia, PA. Presentation entitled “Bridging Sound to Print through Phoneme-Grapheme Mapping” 2005: The Clackmannanshire (Scotland) Report publishes the results of a seven-year study on the effectiveness of bottom-up synthetic phonics in teaching reading and spelling. They are published by researchers Rhona Johnston and Joyce Watson. Three training programs had been conducted with 300 children for 16 weeks, beginning soon after entry to the first year of formal schooling. For 20 minutes per day, children were taught either: (a) by a synthetic phonics program, or (b) by an analytic phonics program, or (c) by an analytic phonics plus phonological-awareness training program. At the end of the 16-week program, the group taught by synthetic phonics were: (a) reading words seven months ahead of the other two groups(b) reading seven months ahead for their chronological age(c) spelling eight to nine months ahead of the other groups(d) Spelling seven months ahead for their chronological age. 2005 – Kathryn Grace was a presenter at the Summer Literacy Institute in Pittsburgh, PA. – Her presentation was entitled, “Helping Children Connect Sounds to Print through Phoneme-Grapheme Mapping. 2005 – Kathryn Grace presented at IDA in Denver, Colorado. Presentation entitled, “Phonics & Spelling Through Phoneme Grapheme Mapping” 2005: Australia publishes its own national inquiry into the teaching of reading, available online here. The study closely follows the lead of the US National Reading Panel in that it rejects Whole Language and, in its place, recommends systematic phonics. Like the NRP, it also recommends an “integrated” approach to reading instruction that includes the Big Five: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. “In sum, the incontrovertible finding from the extensive body of local and international evidence-based literacy research is that for children during the early years of schooling to be able to link their knowledge of spoken language to their knowledge of written language, they must first master the alphabetic code – the system of grapheme-phoneme correspondences that link written words to their pronunciations. Because these are both foundational and essential skills for the development of competence in reading, writing and spelling, they must be taught explicitly, systematically, early and well.” 2006 – Kathryn Grace was a presenter at IDA in Indianapolis, Indiana. Presentation entitled, “Phonics & Spelling through Phoneme-Grapheme Mapping” 2006 – Kathryn Grace created and presented a two day workshop in Lubbock, Texas entitled, “Phonics and Spelling through Phoneme Grapheme Mapping 2006 – Kathryn Grace was a presenter at the National LETRS Institute in Austin Texas. Presentation entitled, “Phonics and Spelling through Phoneme Grapheme Mapping 2006 – Sopris West copyrights Kathryn’s text Phonics & Spelling through Phoneme Grapheme Mapping. 2006: A study found that dyslexics that were taught spelling in a phonetic manner improved their spelling. The study also found that this type of teaching “can actually change their brains’ activity patterns to better resemble the brains of normal spellers.” 2006: Yet another national inquiry, the Rose Report, is published in England. The Rose Report is quite specific about what these four principles of synthetic phonics are: “Having considered a wide range of evidence, the review has concluded that the case for systematic phonic work is overwhelming and much strengthened by a synthetic approach, the key features of which are to teach beginner readers: 1) grapheme/phoneme (letter/sound) correspondences (the alphabetic principle) in a clearly defined, incremental sequence 2) to apply the highly important skill of blending (synthesizing) phonemes in order, all through a word to read it 3) to apply the skills of segmenting words into their constituent phonemes to spell 4) that blending and segmenting are reversible processes.” (section 51) 2008 – Kathryn Grace was a presenter at IDA in Seattle, Washington. Presentation entitled, “Using a Syllable Based Program to Improve Reading and Writing.” Phoneme Grapheme Mapping was presented as a method to teach syllable types and I presented the longitudinal data relative to our implementation of it in our Vermont classrooms over the past decade or more. 2008 – Kathryn Grace was a presenter fir the Cincinnati, Ohio School District. The presentation was entitled, “Phonics & Spelling through Phoneme Grapheme Mapping” 2009: Modern brain imaging methods and recent advances in neuroscience are brought into the mainstream with the publication of Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read by Stanislas Dehaene. While mapping out precisely what happens in the reading brain is still in its early stages, Dehaene’s book affirms 3 important points: “Performance is best when children are, from the beginning, directly taught the mapping of letters onto speech sounds. Regardless of their social background, children who do not learn this suffer from reading delays.” (p227) “The punch line is quite simple: we know that conversion of letters into sounds is the key stage in reading acquisition. All teaching efforts should be initially focused on a single goal: the grasp of the alphabetic principle whereby each letter or grapheme represents a phoneme… Children need to understand that only the analysis of letters one by one will allow them to discover a word’s identity.” (p228) 2010 – The Common Core National Standards are released with a complete section on Foundational Reading Skills which focused on systematic instruction in phonological awareness, phonics, and sight words and stated that these skills are essential for many students and has been proven to accelerate students’ reading development. Effective instruction meets students at their point of need. 2010 – Kathryn Grace presented at IDA in Phoenix, Arizona. The presentation was entitled, “Using Syllable Instruction to Connect Reading and Writing in the Content Areas” Phoneme-Grapheme Presentation was presented as a method to accomplish this. 2011: Stanislas Dehaene’s Article “The Massive Impact of Literacy on the Brain and its Consequences for Education,” explains how the brain processes at the letters in a “massively parallel architecture” and recommends phonics without sight words.2011- Kathryn Grace presented a two day workshop through Cardinal Stritch University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The presentation was entitled, “Breaking the Reading Code with Phoneme Grapheme Mapping”. 2014: A version of Noah Webster’s 1908 Speller is published by Don Potter. Volunteers from 40L used a version of this Speller to teach dozens of students to read above their current reading grade level, including several inner city remedial elementary students who were able to read the 12th grade level passage by the end of their two month remediation class, using the schedule and methods within their spelling program. People were beginning to see that spelling could enhance decoding and vice versa. 2015: A Stanford brain wave study shows how different teaching methods affect reading development, with phonics showing increased activity of the area of the brain best wired for reading.2015 –Phoneme/Grapheme Mapping incorporated into Mindplay’s online reading course, “A comprehensive Reading Course for Teachers”. 2018: The article “Hard Words” by Emily Hanford sparks a new interest and conversation in how reading is taught and the science of reading. Now, states are taking notice and passing new laws to ensure that schools are using research-based reading instruction. Such legislation lands squarely on one side of the reading wars: the side backed by the science of reading. The term “science of reading” refers to the research that reading experts, especially cognitive scientists, have conducted on how we learn to read. This body of knowledge, over twenty years in the making, has helped debunk older methods of reading instruction that were based on tradition and observation, not evidence. Based on the science of reading, the 2000 National Reading Panel Report stated that students need explicit instruction in the essential components of reading: phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension. The key differentiator between the science of reading approach and alternatives is phonics. 2019: The National Right to Read Foundation (NRRF) summarizes the science of reading with updated brain research information.2020: Kathryn Grace creates and presents a webinar for a Facebook Membership group called, The Science of Teaching Reading – What I Should Have Learned in College. Her presentation was entitled, “The How and Why of Phoneme/Grapheme Mapping”2022 – Kathryn Grace signs a new contract with Really Great Reading to publish “Phonics and Spelling through Phoneme-Grapheme Mapping”. 2022: A website is created: phoneme-graphememapping.com |

References for the Historical Dates:

Adams, M.J. (1990). Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning about Print. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Carbo, M. (1996). “Whole Language vs. Phonics: The Great Debate.” Principal. 75,3: 36–38.

Carbo, M. (1988). “Debunking the Great Phonics Myth.” Phi Delta Kappan. 70,3: 226–240.

Chall, J.S. (1967). Learning to Read: The Great Debate. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Goodman, K.S. (1986). What’s Whole in Whole Language? New York: Scholastic.er 31,3: 1.

Grace, Kathryn (1982 to present) A Historical Timeline of Presentations, etc. related to Phoneme-Grapheme Mapping.

Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Slavin, R. (1996). “Neverstreaming: Preventing Learning Disabilities,” Educational Leadership. 53: 4–7.

Willis, S. (Fall 1995). “Whole Language: Finding the Surest Way to Literacy.” ASCD Curriculum Update. Alexandria, VA:Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Whole Language Umbrella. (1997). On the Nature of Whole Language Education. Available http://www.edu.yorku.ca/~WLU/08894f6.htm.